Theoretical physics is such a great field because people from lots of different academic backgrounds can transition into it! Fields that might seem far removed like computer science, engineering and even biology can often lead into theoretical physics. The main two sources of theorists are maths and physics graduates, this can sometimes be a source of worry for both cohorts, I know maths graduates have worried me in the past and still do!

Lets talk about the concerns these two groups might have about how each other could have an advantage over them. After that I hope to at least reduce your worries, whether you are a physics or maths undergraduate. I'll also offer some advice to those of you who are approaching theoretical physics from a subject a bit further away than maths or physics.

Concerns of Physicists:

Lets start with something I know well, fear of mathematicians! I think a lot of the fear physicists have of mathematicians comes from the Cambridge Part III and the number of successful theorists that have come from that maths course. The study of high abstract topics like string theory, super-gravity, super-symmetry and similar topics is seen as being more akin to pure mathematics than physics sometimes. They deal with very generalised situations and use a language not featured in a large proportion of undergraduate physics topics (if any).

Mathematicians often receive in depth training in subjects like topology and differential/algebraic geometry to a high level. These are linked heavily with subjects like string theory and general relativity, so such training is often seen by physics graduates as being a point of weakness on their part.

Furthermore, mathematicians spend a lot of time studying proofs and the art of proof, something physics students definitely DO NOT spend much time on it if any. The impression given is that theorists spend a lot of time proving things and as such physics students get nervous about their lack of experience with proving in a mathematical context.

There can also be a general atmosphere that mathematics is a trickier and purer subject than physics. I have had the idea that maths is superior to physics impressed upon me more than once, it does certainly get you down. Feelings of academic inferiority don't help the previous matters.

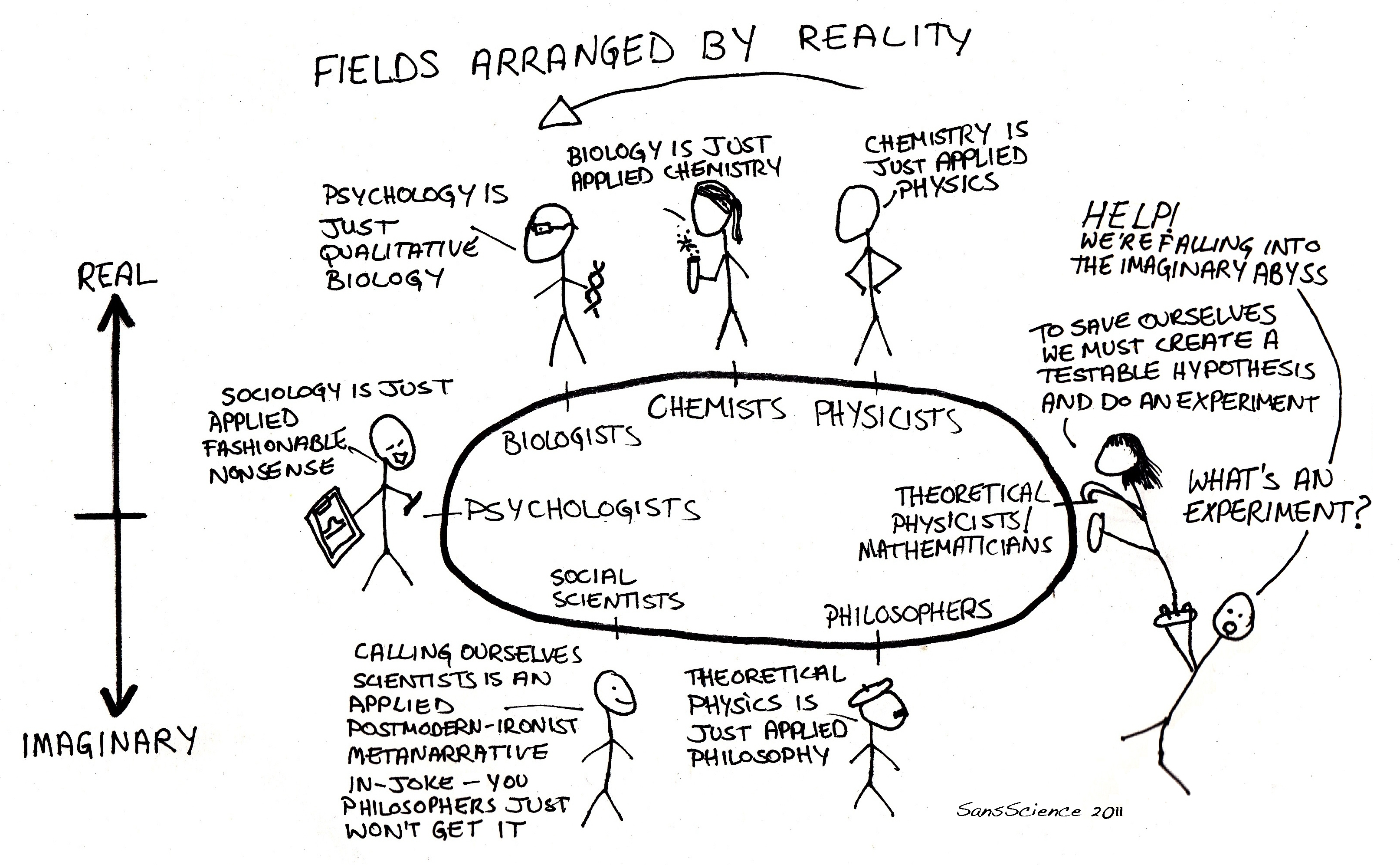

(Image Credit: A Growing Physicist)

Concerns of Mathematicians:

Now not being a mathematician, this is not personal experience I'm drawing on but comments from academics, students from both disciplines and some general logic and know how about maths courses.

Mathematicians are not always trained in advanced classical mechanics. This can appear quite the weakness when compared to physicists who are often trained quite well in the Hamiltonian and Lagrangian formalism by the time they finish their degree! This can be perceived as a weakness when beginning the study of field theory but in reality it is something a mathematician will pick up very quickly.

Physicists have often studied very specific (and highly relevant topics) like particle physics and electromagnetism. Mathematicians might be concerned that they haven't covered the standard model in qualitative detail or Maxwell's equations in depth. Special relativity also comes up, like electromagnetism this is not something necessarily covered in a maths course and a highly relevant topic to many areas of theory.

A more general skill physicists utilise is the contextualisation of mathematical results in a physical setting. Mathematics often does not focus on this, it maintains a more abstract setting (which itself can be perceived as a strength of maths students vs physics students) so mathematicians may fear that lacking experience of this leaves them at a disadvantage.

Like physicists, there can also be a feeling of academic inferiority though for my money I think this affects mathematicians much less. But it does happen, some mathematicians talk about theoretical physicists like they are scary people!

(Image Credit: WordPress)

Addressing concerns...

Firstly... you might notice that each side has plenty of perceived issues. So even if my proceeding comments don't offer you some peace about your perceived disadvantage, know that the 'other side' (for want of a better term) probably have a similar number of completely different deficits to your skill sets. I touched on this when talking about going to a 'non-perfect' uni, everyone, no matter their route, has advantages and disadvantages.

Furthermore, the primary skill you learn in a degree is to, well, LEARN. You can learn skills from maths and physics whichever camp you are approaching theory from. The subjects are not miles apart in the grand scheme of things either, mathematicians and physicists have the closest of languages in comparison to other academic fields. It is not hard for mathematicians to get acquainted with the physical context and interpretation commonly associated with skills acquired through studying physics. Likewise as a physicists you use maths all the time, it isn't hard to pick up a book on topology and starting learning it and the more generalised, proof driven structure of mathematics.

As this cross-over becomes more and more prominent, courses inevitably react as well! Mathematics courses these days often offer modules in quantum mechanics, physics courses also have more advanced maths modules. These supplement perceived weaknesses and can help prepare you for a career in theoretical physics.

I myself took a 'Further Mathematical Methods' module in my 3rd year. It involved studying complex analysis, linear algebra and basic group theory. After this I felt much better equipped to begin venturing into the world of mathematics for theoretical physics.

From my perspective the best thing you can do if you are in the midst of your degree is to (as always) take relevant options to your career path. If you're doing a maths degree take quantum mechanics options, if you're doing physics then take some higher level maths options. Asides from that, don't worry! Both sides have initial weaknesses but these disappear with further study.

With regards to feelings of inferiority, maybe comparison is just a silly idea. Both fields have their own methods and goals, own strength and weaknesses just as their students have.

From my own experience, the criticism levelled at mathematicians by physicists is that their work is too abstract and inapplicable. Any physicist who says this is doing their own field a disservice, development of the language and techniques that physicists (and all scientists) work with on a daily basis is a purely positive thing. No group theory... no standard model, no crystal structure study, no cryptography etc.

Physicists can sometimes get the vibe from mathematicians that their work is not a 'pure' as theirs. This notion of purity and beauty is (sorry to be such a scientist here but) not as yet a measurable quantity. The 'pureness' of a subject is nothing to be concerned about. 'Yes but you haven't proven it in a self contained manner' (to para-phrase), its an irrelevant statement. It's not what physics is about, in the same way that pure mathematicians rarely spend time on applying their work to real world problems, and both of those aspects are ok. And lets not forget that sometimes physicists end up developing serious developments in mathematics (string theory cough cough).

Theorists and mathematicians especially are very close in reality these days so its best not to be comparing ourselves to each other. We should worry more about defending ourselves to the sciences that are do immediate good for the world and explaining why we are still needed!

(Sorry for that rant...)

What if you studied theory and want to go into maths?

This is possible, though I think it's harder than transitioning to theory from maths. If you have covered sufficient mathematical content then it certainly can happen! What I mean by this is by studying GR you can gain experience in differential geometry for example. If you've focused on more numerical topics you might find applied maths fits well and if you've focused on the abstract purer mathematics will probably appeal to you more. Again maths and theoretical physics can be almost indistinguishable at certain boundaries, as a result transitioning from physics to mathematics is not unheard of. But as someone interested in this myself it's not easy to demonstrate you have the pre-requisites to do a PhD in geometry for example. This is only fair though, it's very unlikely that a maths grad would get on an applied particle theory PhD, that's a very real career option for someone like myself.

What if I'm further away from physics than that?

I'm not going to push an illusion here, you would be in a very exclusive (potentially entirely exclusive) group if you managed to do a degree in biology and then end up doing a PhD in say string theory. But for a lot of subjects that might seem a bit further away from theoretical physics, you might be surprised at the areas available to you. Mathematical biology and biophysics are two areas that come to mind when considering moving from traditional biology to a more physics-y direction. Did your degree in geology? Try geophysics. Computer science? Have a look at quantum information and the sub-branches of that. There are a large number of fields like atmospheric physics, physical chemistry and nuclear engineering that can definitely take a theoretical physics perspective. Not all theoretical physics is string theory, in fact most of it isn't!

So whilst I make no promise that anyone/everyone can get a slice of particle theory, I think there are plenty of opportunities for you to get a piece of the theoretical physics pie if you are coming from a different area of science. Sorry English students... I don't think you'll be able to re-specialise this drastically unless you're the next Witten. The key thing is to like (and ideally be good with) maths. Programming is always useful as well.

There you have it, my reasoning for not being afraid of your academic counterparts in other fields within the realms of theory. Ultimately its best to focus on acquiring knowledge and skills and then mastering them. This will put you ahead of your competition, not the nuances of the field you studied.